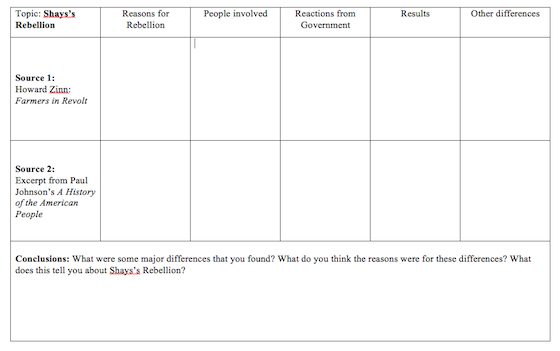

Have you ever mis-heard

something and you had to listen to it again to better understand it? There are

books and websites dedicated to the hilarity of misheard lyrics. My all-time

best misheard song lyric is Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze”. The misheard lyric is

“‘Scuse me while I kiss this guy”. The REAL lyric is “‘Scuse me while I kiss

THE SKY”.

I love misheard lyrics.

They usually make me giggle out loud like a kid. Partly because I mishear

lyrics all the time, partly because they’re so silly and funny, partly because

they make you listen to the song again. I sung “rock the cash box” instead of “rock

the casbah” until well into adulthood!

Here are some of my

other favorite misheard lyrics

Dancing Queen by Abba

Original: See that girl, watch that scene, dig in the dancing

queen

Tiny Dancer by Elton

John

Original: Hold me

closer, tiny dancer

Misheard: Hold me

closer, Tony Danza

(Right. Who’s the boss?)

Rock and Roll by KISS

Original: I want to rock

and roll all night and party every day

Misheard: I want to rock

and roll all day and part of every day

(So much more practical)

Bad Moon Rising by

Creedence Clearwater Revival

Original: There’s a bad

moon on the rise

Misheard: There’s a

bathroom on the right

(good to know!)

All this silliness is to

help us remember that sometimes, you just need to relisten and reread to get it

right. Sometimes, you need to listen to Elton John’s song a few bijillion

times. Sometimes, you need to sing along with the KISS song.

And sometimes, in class,

you need to read a text more than once. Sometimes you need to read it two or

three times.

Ugh.

I admit that even as the

literacy-in-social studies coach, I have pushed back a little against this

read-it-more-than-once trend. I rolled my eyes. I thought I didn’t have time. I

thought my kids “got it” the first time. I thought I had too much content to

teach to stop and reread something.

The eye-rolling was even

more recent than I would like to admit.

And then, I spent a half

of class period on a document from Industrial Revolution mill workers only to

be asked what the Industrial Revolution was and what a mill was immediately. My choice at that point was to either reteach it or grumble about ‘these

kids” and move on without them learning it.

I chose to have them

reread and I’m glad I did.

If you are having your

kids read primary source documents (or more challenging secondary sources), the

chances are pretty good that your kids will get tripped up at some point. It’s

natural. It’s normal. Kids don’t always have the vocabulary, background

knowledge, or reading level to deeply understand every primary source document

you put in front of them.

If they could do it by

themselves, you wouldn’t have to teach it!

Common Core and the new

Florida Standards ask our kids to read complex text deeply. Nobody gets

it right the first time. That’s why they call it complex. And that’s

okay. That’s why second (and third) tries were invented!

Common Core and the new

Florida Standards ask our kids to read complex text deeply. Nobody gets

it right the first time. That’s why they call it complex. And that’s

okay. That’s why second (and third) tries were invented!

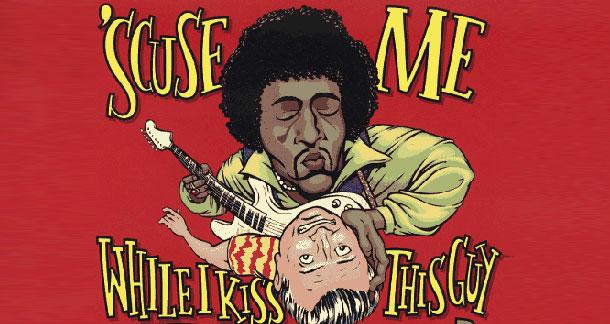

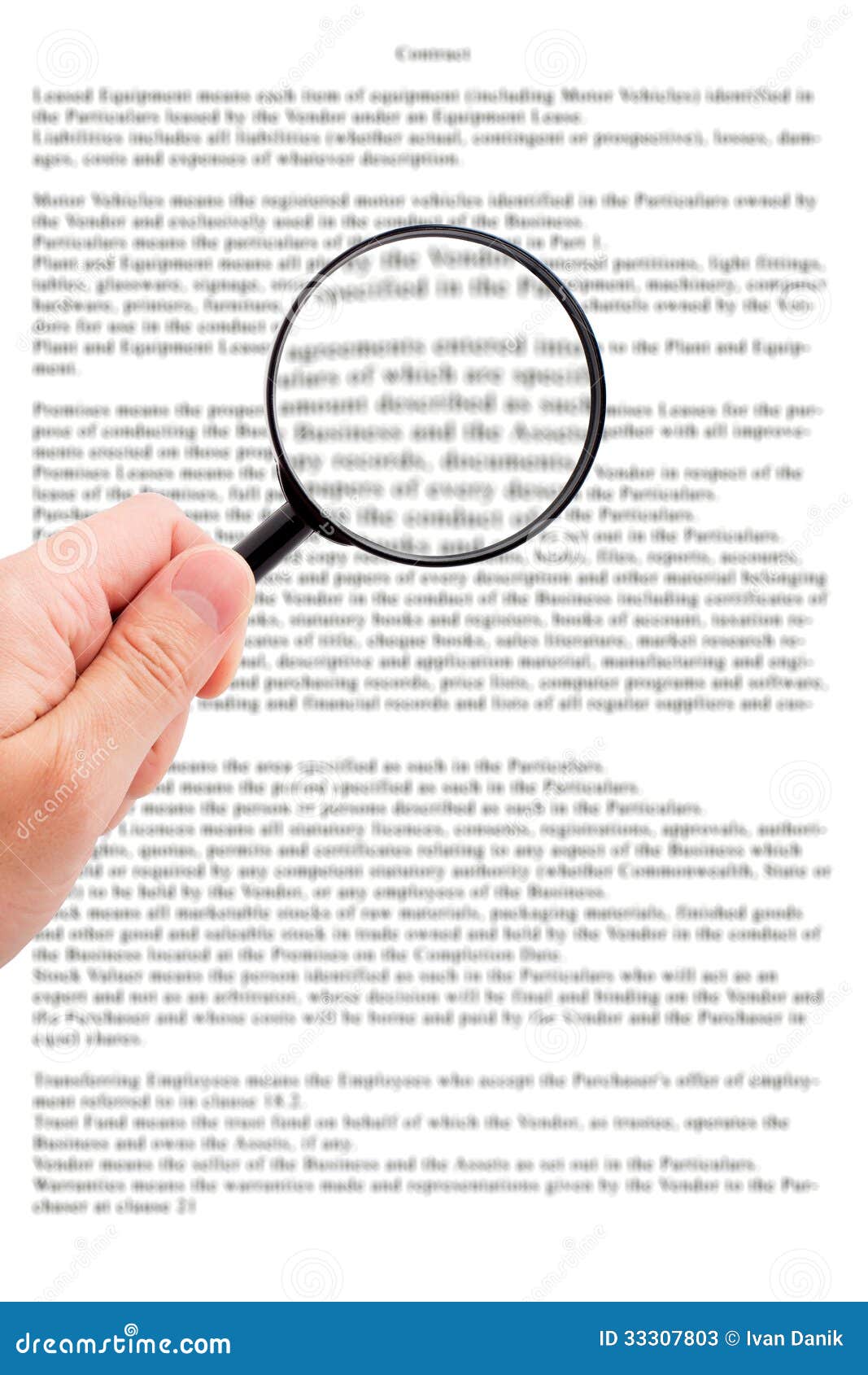

First -- make sure your

document is manageable. If it’s super long, pull out a smaller excerpt. If the

vocab is way above them, annotate it a bit by defining a couple of words in the

margins that are necessary to the understanding of the document (ex.

industrial, mill)

Second -- come up with two

or three separate reasons to read your document. Here are some

examples, but JUST USE two or three

- Overview read -- read the

document silently or teacher read aloud to get the overall idea.

- Text Marking Read -- have kids

use a (?) for parts where they are confused, an (!) for an important piece

of info, an underline for patterns or things that come up

repeatedly, and an --> (arrow) for connecting one piece of text to

another.

- Vocabulary -- have kids read

specifically to find meaning for vocabulary terms (either ones selected by

you or by them)

- Reading Strategy -- have kids

read another time to use your reading strategy (Venn Diagram, for example)

- Essential Question -- have the

kids circle words or phrases that will help answer the Essential Question

of the day.

There are a ton of

different “types” of reads, or different purposes for reading. That’s okay.

PLEASE DON’T... have

kids read it five times (too much!). PLEASE DON’T have kids do these on a long

piece of text (it will take forever).

Instead, choose

two or three of the ones above and guide your kids through a close

reading in which they read the document more than once.

We all have to read

things more than once. It’s why millions of books or sermons are written on the

same pieces of holy writings. It’s why people can read Shakespeare (or even

their favorite novels) again and again. It’s why every time I look at a great

work of art, I see something I missed last time.

There’s no shame in

rereading. It’s not just for lower-level kids. There’s honor and pride

and rigor in multiple reads -- or IKEA directions or song lyrics or (hopefully)

in primary and secondary documents.

It’s important to read

important or complex texts more than once. There are several ways to do that.

So, will you try it? Start with something complex but brief -- something like a

short letter or the Preamble or a paragraph from a historian.

Please drop me a line and let me know how it goes. And, please, hold me closer, Tony Danza!

-Tracy